|

Review II

Nicholas H. Ruth

Statement on Scholarship

For as long as I can remember, doubt has been a compelling motivator for me. My broad curiosity and general perplexity about the nature of things is in constant dialogue with possible explanations; this is a rich as well as an anxious conversation. As a painter, I tend to spatialize my existential conflicts. The single constant that I have encountered in this fluid yet mappable world is that positions-both spatial and philosophical-are understood not as absolutes but in relation to others. In this context, I see my work as a metaphorical response that attempts to make some sense of what is so complicated, and to make coherent the brimming energy of uncertainty.

Towards this end, I use a complexity of formal relationships to create visually dense images that inspire reflection on surety, ambivalence, and doubt. Specifically, I am interested in making work that is unified, intelligible, and aesthetically beautiful at the same time that it expresses a feeling of shifting frames of reference and the fleeting nature of certainty. At the most personal level, my work makes manifest my experience that a single event can be understood in a disorienting number of ways. These goals are philosophical and conceptual and I delight in the interplay between theory and practice in the making of my work.

The methodological context for my work is the blending of elements from several historical and contemporary models. My greatest debt is to European and American Modernism, from which I draw a love of visual perception distinct from narrative content, a delight in paradox, and an appreciation for beautifully articulated subjective expression. I have also been influenced by postmodernist theory and analysis, and by the critique of systems of meaning. These influences percolate through my process, and become discernable to me mostly after I have already come to a visual decision about the completion of a piece. Currently, my work is abstract, geometric, patterned, visually dense, and technically precise and involves the juxtaposition of several modes of Western spatial representation. In the near future, I plan to continue to make images that provide a concentration of visual experience, while exploring a looser technical approach and introducing non-Western conventions of signifying space.

Current Work

I make paintings, drawings, prints, and digital images because I am deeply moved by creative exploration (as a viewer and as a maker), and because I am drawn to the visual in particular. I am drawn to the manipulation of the materials themselves. I am also drawn to the subtlety of visual perception. In exploring various media and in exploring visual perception, through trial and error, I find materials, imagery, and formal structures that I recognize as successful. Through practice and experience, I have become visually sophisticated, and I work to satisfy my own sense of what is compelling. My goal is to achieve a sophisticated subjective expression that will be meaningful to others because I thoughtfully use culturally constructed and shared conventions of pictorial organization and because I simultaneously bend, build on, and break those conventions in order to discover a more exact expression of my experiences.

Notwithstanding preconceived intentions, it is the actual making of the work-the marking and the looking and then the recognition-that leads to insights and new ideas. My process is less a matter of executing plans and more a question of positioning myself to make discoveries. It is important to state this primacy of the physical and the perceptual (and also of the exploratory nature of my process) at the outset because it helps to contextualize my own practice within historical and contemporary art practices. It is also important because my interests in phenomenology, epistemology, semiotics, art history, and cultural studies are easier to articulate than the essentially inexpressible ways in which artists make choices, and in which art becomes meaningful. My process is an interdependent mix of the physical, the perceptual, the intuitive, and the analytical.

The work that I admire the most, that is most meaningful and influential to me, is work that visually expresses paradox. In my own work, I have become fascinated by the notion of point of view, of multiple points of view, and of the possibility of juxtaposing multiple points of view as a way of exploring the relativity of experience. In my work, point of view refers both to an implied physical position for the viewer, such as the specific location implied by linear perspective or the almost omniscient position suggested by an isometric projection, and to different modes of representation and spatial organization, such as the rendered three-dimensional forms of illusionism or the optical "push and pull" of Hans Hoffman's Modernism. These notions of points of view stand in for yet others, in which point of view refers to a stance or set of beliefs. By juxtaposing different points of view within a unified image, I am able to visually express the paradox that I find so compelling and that is so central to my own experience.

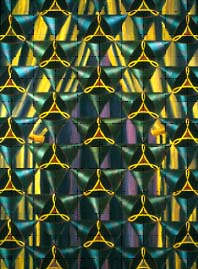

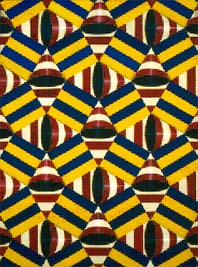

The painting "La Robe à Ramages" (2003, oil on panel, 48" x 36") is an example of what I am describing. An initial glance absorbs the overall pattern of triangles and cones. The painting, however, consists of three different, overlapping spatial idioms: the illusionism of the cones, the coarse realism of the curtains behind, and the optical hovering of the yellow modified trifolium shapes in the middle of the openings of the cones.

For the painting to work, none of these idioms can appear dominant, nor can they operate in complete distinction from one another, nor can they fold into a single seamless system. They must slowly protest each other, and provoke more looking and effort to try to resolve the constructed tension. More looking brings awareness of yet other things: the move of the cones from a warm emerald green in the center to a cool viridian at the edges, the presence of the impastoed curtain belts, the spatial ambiguity of the connection between the yellow ochre of the curtains and the yellow ochre of the modified trifolium shapes.

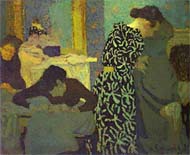

An integral aspect of making my own work, looking at art broadens the scope of my visual experiences, trains my eye, and informs my sense of culture and history. "La Robe à Ramages" is an example of my love and appreciation of the works of other artists. It is an homage to the French painter Eduard Vuillard, who made a painting of that name in 1891. Vuillard is known in part for painting society portraits and decorative landscapes, but his more significant contributions were his genre paintings of interior scenes with his family and friends. They are significant for the delicate and sophisticated way

s

in which they vacillate between a carefully structured representational

illusion of space and an equally nuanced approach to the abstract configuration

of visual elements such as shape, color, and pattern. The tension between

an illusion of space and the fact of the essential flatness of the paint

and canvas is inherent to the visual perception of painting, and is a

rewarding lens through which to approach all two-dimensional art. It is

especially important for the consideration of Modernist art. In my opinion,

Vuillard was among the best practioners of this important aspect of Modernism.

s

in which they vacillate between a carefully structured representational

illusion of space and an equally nuanced approach to the abstract configuration

of visual elements such as shape, color, and pattern. The tension between

an illusion of space and the fact of the essential flatness of the paint

and canvas is inherent to the visual perception of painting, and is a

rewarding lens through which to approach all two-dimensional art. It is

especially important for the consideration of Modernist art. In my opinion,

Vuillard was among the best practioners of this important aspect of Modernism.

Vuillard is also known as a painter of intimacy. The gorgeous formal structuring of his work seems entirely synchronous with his scenes of family and friends deeply absorbed in their daily lives. The actual activities of the people in the paintings is inseparable from the manner in which they are depicted; women at work, families at table, and people often in the same room but quiet and in their own thoughts all mesh with the low light and shifting patterns of wallpaper and fabric. The scenes have an indirect narrative, and describe a gentle humanity. I, too, am interested in the possibility of an indirect narrative, a narrative presented primarily by the formal structures and contrasting spatial modes of the image and only then augmented by the potential for symbolism. Initially, I painted the curtain in the back of "La Robe à Ramages" to visually push against the screen of cones. It is a curtain because I had just re-read an essay by the art critic Clement Greenberg in which he uses the analogy of a curtain to describe some of the goals of Modernist painting. The curtain can also refer to the drapery of a dress, as in the title of the painting. Ultimately, I am aware that the curtain can further symbolize concealment and revelation, and that it can symbolize the artifice of theatrical performance. These are connections that I have considered, that I find personally meaningful, and that I think are among the set of connections potentially available to a viewer. I do not, however, consider them prerequisite to understanding the painting; looking is what is required for that.

Understanding historical movements and grappling with contemporary practices can help create a useful context for further understanding my line of inquiry and the influences which have helped to shape it. My work is best described as a blending of Modernist and Postmodernist concerns. Modernism is often defined as involving a rational but subjective self, self-consciously and empirically reasoning toward an elusive system of meaning. In the visual arts, Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse, Pollock, and DeKooning are considered exemplars of Modernism. Postmodernism, on the other hand, assumes all meaning to be constructed and therefore biased, and often uses strategies of appropriation, juxtaposition, re-framing, and irony to topple pretensions of objectivity and certainty. My work is based in the self-conscious and empirical practices of Modernism, and in the suspicion of claims of objectivity underlying much Postmodernist art.

Modernist art has been very influential to me. I find the formal structures characteristic of Modernism thrilling to look at, and the conceptual concerns compelling to think about. Postmodernist art, on the other hand, has been important to me mainly for thinking about. I don't find the aggressively disorienting qualities, illustrational tendencies, and ironic stance of much postmodernist art compelling, but I am drawn to the critique of systems of representation. So, while some of the thinking behind Postmodernism seems relevant to me, my use of juxtapositions is not ironic. Postmodernism uses juxtapositions to cancel out opposing notions of truth. I use juxtapositions because I suspect that truth is somewhere in the middle.

The painting "Metasemaphore" (2003, oil on panel, 36" x 27") is another

way to describe what I am interested in. The painting rests on the basic

play between the illusion of volume in the cones, the flatness of the

stripes, and the optical space created by the interaction of the colors.

Retrospectively, I am aware that in this painting, and all of my work,

I draw on specific aspects of a number of (primarily) late 20th century

approaches to painting. For instance, I have a debt to the visually kinetic

effect of the Op Art of the 1960s, though I am less interested in the

intensity or speed of it. I also work in territory explored by the Pattern

and Decoration painters of the 1970s and 80s, whose work brought the beauty

of pattern into the mainstream of fine art and challenged the gendered

politics of fine art versus craft. I am a beneficiary of that fight on

both accounts, but I do not use pattern or decoration for political reasons.

My work also relates superficially to the Neo-Geo painting of the 1980s

and 90s, but I am more affected by the trompe l'oeil of Harnett, the delicacy

of Schwitters, the power and elegance of Serra, and the romance of Klee.

What is ultimately important about these references is that they are a

set of tools, of ways of looking and ways of structuring visual relationships

that I can use intuitively as I make a picture, playing one off against

another as I look for my own way to create a multivalent visual experience.

way to describe what I am interested in. The painting rests on the basic

play between the illusion of volume in the cones, the flatness of the

stripes, and the optical space created by the interaction of the colors.

Retrospectively, I am aware that in this painting, and all of my work,

I draw on specific aspects of a number of (primarily) late 20th century

approaches to painting. For instance, I have a debt to the visually kinetic

effect of the Op Art of the 1960s, though I am less interested in the

intensity or speed of it. I also work in territory explored by the Pattern

and Decoration painters of the 1970s and 80s, whose work brought the beauty

of pattern into the mainstream of fine art and challenged the gendered

politics of fine art versus craft. I am a beneficiary of that fight on

both accounts, but I do not use pattern or decoration for political reasons.

My work also relates superficially to the Neo-Geo painting of the 1980s

and 90s, but I am more affected by the trompe l'oeil of Harnett, the delicacy

of Schwitters, the power and elegance of Serra, and the romance of Klee.

What is ultimately important about these references is that they are a

set of tools, of ways of looking and ways of structuring visual relationships

that I can use intuitively as I make a picture, playing one off against

another as I look for my own way to create a multivalent visual experience.The Development of My Work

My current work represents a point on what I hope will be a long and rewarding line of inquiry. When I came to Hobart and William Smith as an adjunct professor in 1995, I was already involved with pattern, and with a compression of spatial illusion created by a physical, textured paint surface and by paradoxical play with scale change and color relationships. In "Sky's the Limit" (1995, oil on canvas, 48" x 48"),

I

placed gestural as well as stenciled and taped marks and shapes into a

web of loose pattern. The overall pattern sets up an expectation of order

and orderliness. The structure of overlap, "erased" areas, shifting size

of diamond shapes, and color relationships all challenge and complicate

that expectation.

I

placed gestural as well as stenciled and taped marks and shapes into a

web of loose pattern. The overall pattern sets up an expectation of order

and orderliness. The structure of overlap, "erased" areas, shifting size

of diamond shapes, and color relationships all challenge and complicate

that expectation. Around this same time, I began to use stencils and masking tape in my work as a way of minimizing the importance of my personal touch or gesture in the work. I felt that the presence of my hand, of my autographic mark, was a distraction from the more important question of the formal structuring of space. The mechanical, cold, and hard quality of the resulting marks helped me to not feel caught up in whether or not my hand-made marks were good enough. While I quickly came to see that I was simply substituting one kind of hand for another, this desire to be able to see things freshly and clearly has been very important in my work, and has manifested itself in a number of significant ways.

The most important way in which my desire for critical distance has impacted my work is through my exploration of a number of different media. I was initially trained as a photographer when I began my art studies in college, and I have proceeded to investigate drawing, printmaking, painting, sculpture, digital imaging, and bookmaking as avenues for artistic expression. This way of working is a bit nomadic, with the attendant problems of not getting to know one method exhaustively, but for me the benefits have far outweighed the costs. Drawing has been central to my work, because of its rich tradition as an exploratory process, and because it is so graphic and immediate. Printmaking has been crucial, both because I feel an affinity for the particular visual qualities of intaglio prints, but also because the methods of printmaking tend to enforce a process of working in stages, a critical distance. In many printmaking processes, one works on a plate for a while, not knowing for certain how the work will look in the print itself. The making of a proof, a print of the plate in its current condition, makes visible what was only speculation before. The physical manipulation of the materials of printmaking is as interesting and rewarding as that of painting and drawing, but the necessary division of the work of printmaking into stages is utterly different than the immediacy of paint or charcoal. Printmaking provides enforced moments of pause, opportunities to deliberate and be deliberate. In this way, printmaking has informed my approach to painting and drawing, just as my love of the immediacy of painting and drawing has helped me to avoid being overly technical in printmaking.

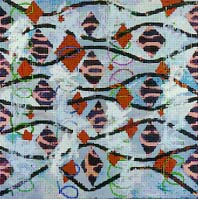

By 1999, I had begun to explore digital imaging as another way of testing my ideas. At that time, the

patterns

in my work had become fairly regular and consistent, and I was layering

them over one another in such a way that they would compete for visual

prominence. I was still using tape and stencils as a means of getting

a different kind of mark, and I incorporated those stencils, as well as

bits of photographs I would take, into my new experiments with digital

work. I was especially drawn to the possibilities of the computer once

I realized that the preeminent software for image making, Adobe Photoshop,

was based on the concept of layers and the ability to manipulate layer

order and opacity. "Untitled," (1999, digital Iris print, dimensions variable)

is an early example of this work. In it, I layered scans of stencils that

I was using in the making of my paintings, with scans of ribbon and other

computer-generated imagery. While the primary advantage of using the computer

was in having yet another way to look for the specific perceptual paradoxes

I recognized as important, it also encouraged me to re-introduce photographic

(and therefore highly illusionistic) material into my work.

patterns

in my work had become fairly regular and consistent, and I was layering

them over one another in such a way that they would compete for visual

prominence. I was still using tape and stencils as a means of getting

a different kind of mark, and I incorporated those stencils, as well as

bits of photographs I would take, into my new experiments with digital

work. I was especially drawn to the possibilities of the computer once

I realized that the preeminent software for image making, Adobe Photoshop,

was based on the concept of layers and the ability to manipulate layer

order and opacity. "Untitled," (1999, digital Iris print, dimensions variable)

is an early example of this work. In it, I layered scans of stencils that

I was using in the making of my paintings, with scans of ribbon and other

computer-generated imagery. While the primary advantage of using the computer

was in having yet another way to look for the specific perceptual paradoxes

I recognized as important, it also encouraged me to re-introduce photographic

(and therefore highly illusionistic) material into my work.Insofar as digital imaging allows me to generate multiple identical copies of an image and output them onto paper, using the computer is an extension of my work in printmaking. However, the value of imaging technologies for me has had more to do with two other things, the first of which is the computer as a model of information architecture. While I am not especially technologically inclined, I am aware of the way in which the internet, hypertext, and much contemporary art that relies on interactive computer software often explore a non-linear approach to information, experience, and understanding, and such work has strongly influenced my thinking.

The second important way in which computers have been valuable to me is process related, specifically the ease with which one can do otherwise very tricky things. For instance, to experiment in paint with different configurations for the curtains in my painting "La Robe à Ramages" would have taken weeks of work. To take a digital photograph of the painting, gather examples of curtains from the internet, and experiment with different possibilities (as I did) took a matter of hours. In my most recent digital images, I experimented with color in ways that would have been essentially impossible had I been working with paint. I have also been recently inspired to use the computer to further my experiments with illusionism, or three-dimensional rendering. Three-dimensional rendering programs are capable of producing very complex effects with relatively little effort, and the challenge for me has become the reverse of my challenge in other media. While in painting and printmaking I work hard to make the illusion of three-dimensionality strong enough to create tension with the flatness of the surface and the optical ordering of colors in space, in digital imaging the illusionism is so strong and convincing in a photographic sense that I have to work hard to find ways to make the surface seem flat at all, and to help the colors operate with some independence from the three-dimensional forms they describe.

Although I have thought extensively about it, I cannot explain with absolute certainty why I have started to use illusionism in my work. I think that it is because I wanted to find a way to more gracefully fuse the

different points of view in each image, while simultaneously increasing

the potential for disruption. In my work during the 90s, I depended on

an interpenetration of patterns, such that each shape belonged to several

patterns. By contrasting various aspects of color (such as hue, value,

and intensity), a shape might seem to cohere with one pattern at one moment

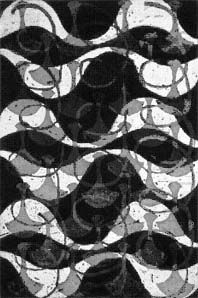

and a second in the next. When making intaglio prints, such as "Untitled"

(1998, intaglio, 18" x 12" image), I used value contrasts and the power

of implied line. One first perceives the strongest contrasts, created

by the value contrast of the light and dark undulating horizontal shapes.

One is aware that those shapes are not homogenous, and attention to the

other shapes within the undulating shapes points to the pattern of pendulum

shapes and finally to the pattern of three vertical coils. By manipulating

contrast in this way, I created an experience of visual unfolding as each

shape configured with successive layers of pattern, and became distinct

from the others and from the initial apprehension of the image. In my

current work, there is less layering of pattern and everything happens

at once, in one continuous field. To the extent that any given shape or

form is doing more than one thing,

different points of view in each image, while simultaneously increasing

the potential for disruption. In my work during the 90s, I depended on

an interpenetration of patterns, such that each shape belonged to several

patterns. By contrasting various aspects of color (such as hue, value,

and intensity), a shape might seem to cohere with one pattern at one moment

and a second in the next. When making intaglio prints, such as "Untitled"

(1998, intaglio, 18" x 12" image), I used value contrasts and the power

of implied line. One first perceives the strongest contrasts, created

by the value contrast of the light and dark undulating horizontal shapes.

One is aware that those shapes are not homogenous, and attention to the

other shapes within the undulating shapes points to the pattern of pendulum

shapes and finally to the pattern of three vertical coils. By manipulating

contrast in this way, I created an experience of visual unfolding as each

shape configured with successive layers of pattern, and became distinct

from the others and from the initial apprehension of the image. In my

current work, there is less layering of pattern and everything happens

at once, in one continuous field. To the extent that any given shape or

form is doing more than one thing,  it

is because that shape or form represents more than one spatial idiom or

mode of representation. Thus, in "Kilter I" (2002, intaglio, 24" x 18"

image), the space is shallow and compressed, and there is tension between

the contour and rendering of the cones, which create the illusion of volume,

and the continuity of the stripes which has a flattening effect. If the

balancing and overlap of spatial idioms is successful, then the image

is both easier to take in initially and harder to resolve in any finite

way.

it

is because that shape or form represents more than one spatial idiom or

mode of representation. Thus, in "Kilter I" (2002, intaglio, 24" x 18"

image), the space is shallow and compressed, and there is tension between

the contour and rendering of the cones, which create the illusion of volume,

and the continuity of the stripes which has a flattening effect. If the

balancing and overlap of spatial idioms is successful, then the image

is both easier to take in initially and harder to resolve in any finite

way.The development of my work has been a cumulative rather than reactive process. Not since graduate school have I abandoned one way of working in favor of another, and even in that case I think that the change from representation to abstraction did not alter what I really wanted from my work. The more or less recent introduction of illusionism into my work is an example of a slow turn, and I expect that this is the way that I will continue to work.

The Future Direction of my Work

Concurrent with my interest in the juxtaposition of spatial idioms has been a re-emergence

of

my interest in the art of other cultures. I have long been fascinated

by the dazzling use of pattern in Muslim cultures and in the textiles

of various cultures in Africa. However, I am even more drawn to consider

the way in which different cultures choose to represent space. While the

legacy of linear perspective continues to dominate the visual culture

of the west, the visual heritages of China and India, by eschewing mimesis

in favor of more symbolic representations, point to other ways of envisioning

the self and the world. Inspired by my fascination with Chinese landscape

painting, I have recently begun a series of intaglio prints in which I

aim to introduce yet more idioms of spatial organization. I hope to be

able to begin to break the rigorousness of some of the patterns in my

work and play some more unexpected elements into the visual dialogue,

as in this untitled print ("Untitled," 2004, intaglio, 9" x 6" image).

In this image, elements of pattern overlap others and are also interrupted

by negative spaces that read as clouds or mist. I have also used atmospheric

perspective, in which forms that are farther away look lighter than those

that are close, to enhance the tension between the essentially shallow

space of the patterns and the implication of scale and distance that the

clouds introduce.

of

my interest in the art of other cultures. I have long been fascinated

by the dazzling use of pattern in Muslim cultures and in the textiles

of various cultures in Africa. However, I am even more drawn to consider

the way in which different cultures choose to represent space. While the

legacy of linear perspective continues to dominate the visual culture

of the west, the visual heritages of China and India, by eschewing mimesis

in favor of more symbolic representations, point to other ways of envisioning

the self and the world. Inspired by my fascination with Chinese landscape

painting, I have recently begun a series of intaglio prints in which I

aim to introduce yet more idioms of spatial organization. I hope to be

able to begin to break the rigorousness of some of the patterns in my

work and play some more unexpected elements into the visual dialogue,

as in this untitled print ("Untitled," 2004, intaglio, 9" x 6" image).

In this image, elements of pattern overlap others and are also interrupted

by negative spaces that read as clouds or mist. I have also used atmospheric

perspective, in which forms that are farther away look lighter than those

that are close, to enhance the tension between the essentially shallow

space of the patterns and the implication of scale and distance that the

clouds introduce.I am very excited about these ideas, and eager to investigate them. If I am granted tenure, I intend to apply for a sabbatical leave for the 2005-06 academic year, during which I would explore these new developments with the three-dimensional rendering software that I described above, and also in a cycle of large paintings, drawings, and traditional prints. I am optimistic that opening up my process to more accident and play will help me to bring more of the surprise and insight that I long for into my work.

Exhibitions and Scholarly Endeavors

My scholarship consists of my creative work in the studio (paintings, drawings, prints, and digital images), exhibitions of this work (solo, group, invitational, regional juried, and national juried exhibitions), lectures and demonstrations on my art given at schools and conferences, collaborations with other artists, and work curating or co-curating exhibitions. My scholarship also involves travel to study both contemporary and non-contemporary art, reading in my field (books and journals about art, artists' monographs, and exhibition catalogs), and the pursuit of grants to fund my work.

A crucial aspect of my efforts as an artist is getting my work exhibited so that people can see it. Typical outlets for me are college and university galleries and community art centers. I have sought a balance among three types of exhibition opportunities: solo exhibitions, in which I am able to show a significant amount of my work and have control over its installation; two person or small group exhibitions, in which I show a body of work in dialogue with that of other artists; and large group exhibitions, where my work is seen in the context of an array of art by an array of artists. Because of my control over the installation of my work, solo shows have the advantage of making the exhibition an extension of my intentions within the work, while group shows help to make my interests clear by contrast with those of other artists. I have sought group exhibition opportunities that I thought would put my work in good company, would include my work in an interesting investigation of an idea or approach, and were being juried by interesting and expert jurors.

Since arriving at HWS, I have had 9 solo or two person exhibitions. In that same period I have been asked to exhibit in 8 invitationals, and have had work accepted into 3 regional juried exhibitions and 9 national juried exhibitions.

Lectures, demonstrations, and visiting artist opportunities are another aspect of my scholarship. In the last four years, I have been invited to present my work at six schools around the nation. In 2003, I conducted a workshop called "Photoshop as Process: Looking Beyond Special Effects," at Westmoreland Community College, and co-presented a paper in 2002 with Professor Michael Tinkler called "Voices from an Art Department," at the Blackboard: Building a Community of Learners conference at St. Lawrence University in Canton, NY.

Collaboration has provided me with opportunities for unexpected growth in my work. In 1999-2000, I worked with Professor Donna Davenport of the Dance Department and a group of student dancers on an interdisciplinary project that explored my ideas about pattern and relativity. This collaboration in a time-based discipline helped me reconsider my ideas about narrative structure.

Curating exhibitions has been another important scholarly avenue for me. Curating allows me to explore interesting developments in contemporary art and then present what I find to the community. It also helps me to engage and develop relationships with artists and colleagues from other institutions, through dialogue about contemporary art and through the inclusion of their work in the resulting shows. Finally, curating exhibitions provides an invaluable teaching tool by giving students direct access to contemporary art by professional artists. Since arriving at HWS I have curated exhibitions on the state of contemporary abstract painting ("Abstract Matters," 1995), artists working with digital imaging and new media ("v.1: artists working in digital media," 1999), and current trends in contemporary painting ("Concurrence," 2001). In 2003, I co-curated, with artist Karen Sardisco, another exhibition called "re/order," examining the work of artists who restructure imagery and information. All of these exhibitions took place at the Houghton House Gallery ("re/order" also traveled to the Mercer Gallery at Monroe Community College in Rochester, NY).

I have twice received grants from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA), once to pursue my work and exhibit it in the community and once to direct a children's mural project at the Geneva Free Library. I also received a Special Opportunity Stipend grant from NYSCA to produce and exhibit a cycle of digital images in Ithaca, NY. I have also applied for grants from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Elizabeth Foundation, and the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts.

A final but very important aspect of my work is my travel to see art. While my curatorial efforts have helped me keep informed of recent developments in the field, it has been my trips to New York City to look at art in galleries and museums and my conference attendance and participation that have been most important. While I have also continued to read contemporary art journals to sustain connection to criticism and theory, there is no replacement for actually experiencing the work and interacting with its practitioners. I have returned from New York City and my other travels impressed, amazed, infuriated, informed, and invigorated. These trips have had a direct and positive impact on my work.

Any questions regarding this site can be emailed to nruth@hws.edu

This site is best viewed in Internet Explorer at 800X600